Aquaculture. land-based or sea-based

Ken Chan

In March 2019, then Minister for the Environment and Water Resources Masagos Zulkifli revealed Singapore Food Agency’s (SFA) ‘30 by 30’ goal – “…to sustainably produce 30% of the nation’s nutritional needs locally by 2030”. An ambitious target, given that currently 90% of Singapore’s food supply is imported, with only about 1% of Singapore’s land set aside for agricultural use. Such an ambitious end goal necessitates an innovative use of technology given Singapore’s space constraints, and implies an aggressive need to intensify land use either by way of heightening space or yield. With vegetables and fruits, we’ve already seen yields scale with the advent of vertical farming (e.g. Archisen), but the considerations are profoundly more complex where livestock is concerned. Here, we take a curious glimpse into the local aquaculture scene, spurred by our friends at Atlas Aquaculture.

History

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, total fisheries and aquaculture production (excluding algae) globally has grown from 19mt in 1950 to 178mt in 2020. While the phenomenal growth may not seem surprising against the backdrop of the global population boom over the same period, what struck us has been the share of aquaculture in that growth – of the 178mt produced in 2020, 49% came from aquaculture – a sea change (pun intended) from a mere 4% in 1950. Accompanying that growth has also been a significant geographic redistribution of total production – in 2020 Asia accounted for 70% and China a whopping 35% alone. Asia has been the dominant force in aquaculture through the decades, garnering 88% of total production from aquaculture in 2020.

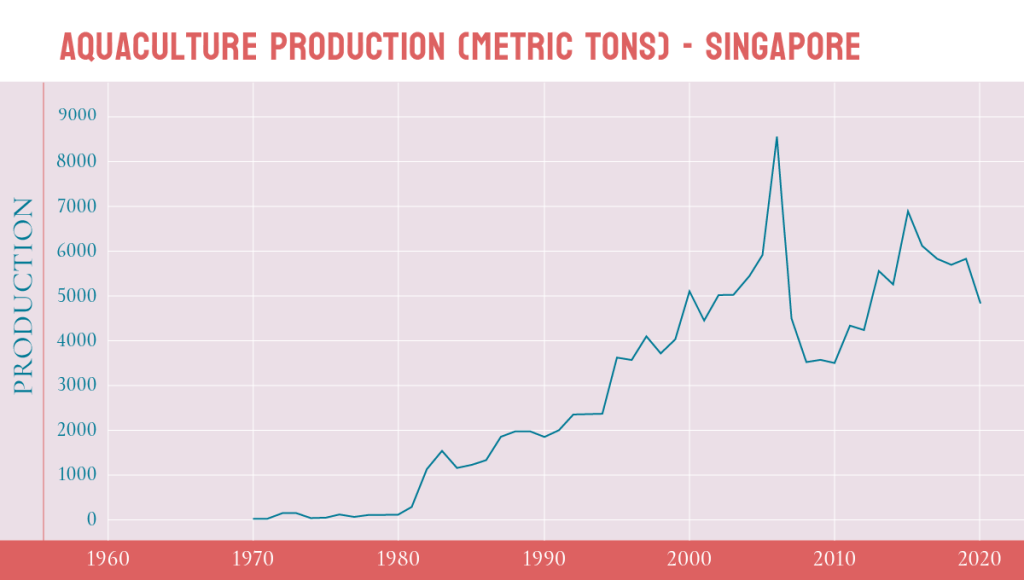

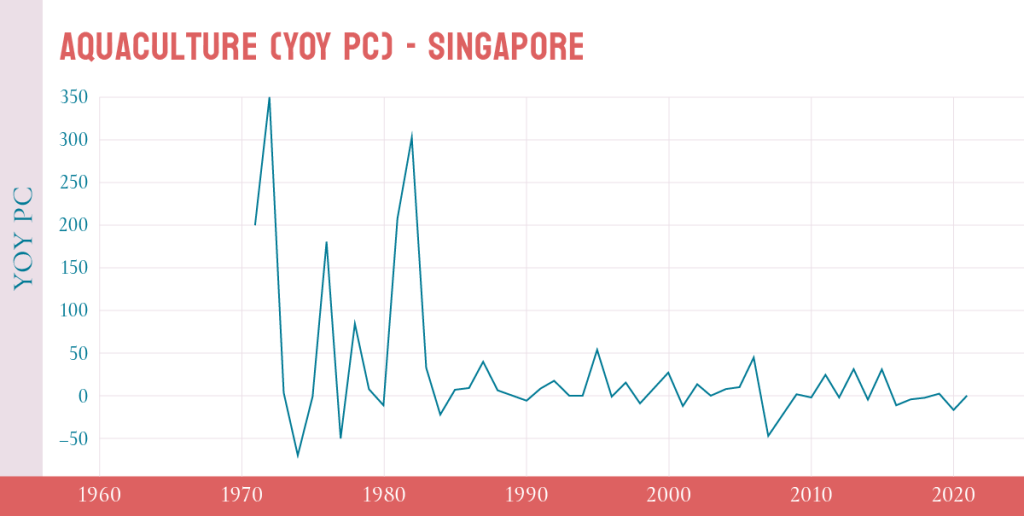

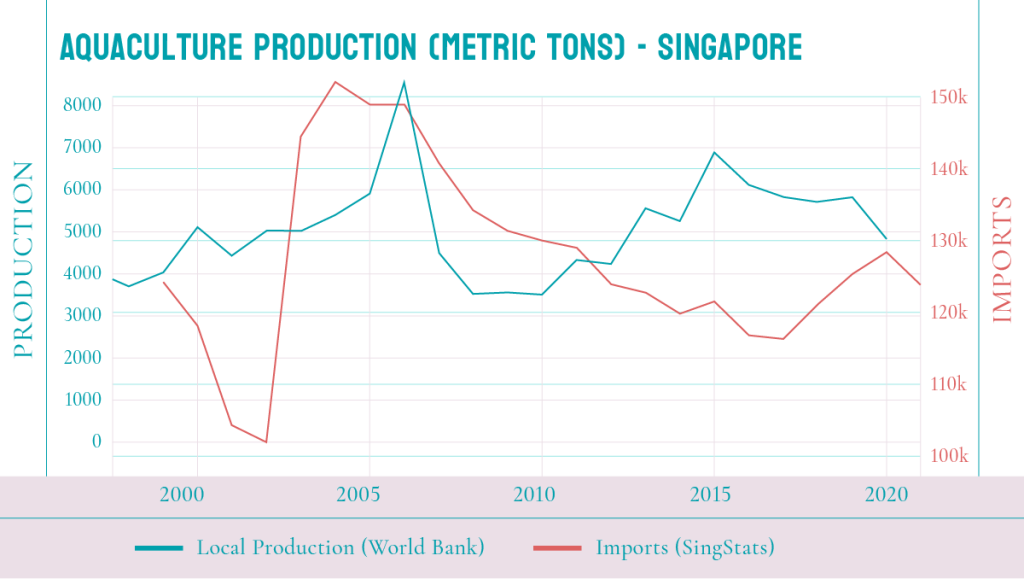

In this context, it was perhaps not unexpected to see a similar trend of growth in the World bank data for Singapore. Aquaculture production on (and around) our island has grown exponentially since 1970, reaching a peak of 8573 in 2006 before the abrupt declines in 2007-9 and subsequently in 2014-15.

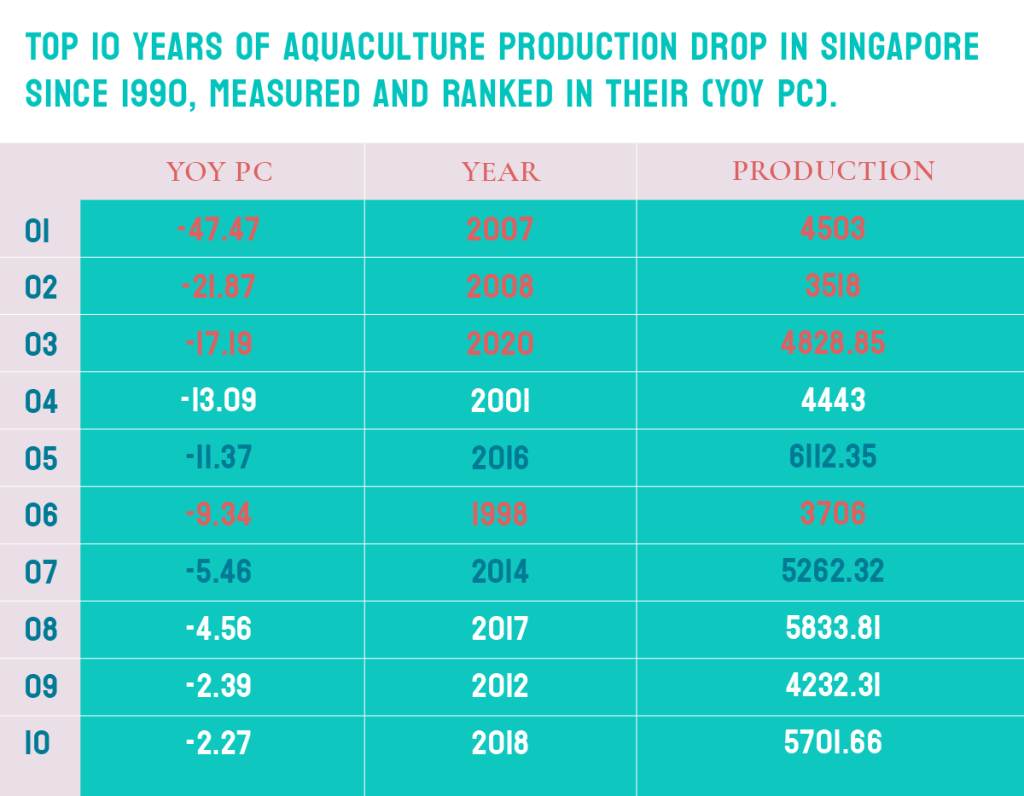

Table below shows the top 10 years of aquaculture production drop in Singapore since 1990, measured and ranked in their (YOY PC).

Prima facie, the largest declines in aquaculture production occurred during the financial crises periods of low growth – 1998 AFC, 2007-2008 GFC and 2020 Covid-19 pandemic. The production declines in periods of financial stress have even outpaced the declines brought on by physical environment changes – the plankton bloom wiped out several coastal aquaculture farms during the period 2014-15 which made subsequent recovery even more difficult.

Singapore’s Aquaculture Landscape

The plankton bloom that devastated the aquaculture industry in 2014-15 triggered a shift towards land based inland aquaculture, with some using recirculation systems where water quality and other key breeding parameters could be controlled. Singapore has 110 licensed coastal aquaculture farms (sea-based), and 27 land-based farms producing a total of 5.0 thousand tonnes of seafood.

30% of the aquaculture farms here are owned by corporations, with the remaining 70% by individuals. Arguably, the lopsided proportion of individuals running such farms runs contrary to the establishment’s hope for larger and better resourced corporations to build and operate these farms to achieve the scale required (a similar strategy that has been run for our local banks in the early 2000s) – swim or sink against the tide of larger multinational corporatised farms. While pointless, the postulation here is that aquaculture production would have experienced a much stronger growth over the same period had the proportions between corporates and individuals been reversed. One need only look at the SFA guide “Starting a Sea-Based Farm: An Industry Guide”, to appreciate that any such endeavour was not meant for individuals (or non-suicidal families). In the SAFEF’s Foreword “….I urge you to garner your team of technical experts such as a Naval Architect, a Professional Engineer and other Qualified Persons….” and subsequently in the guide, it’s clear that no less than 6 and possibly more than 10 agencies require regulatory clearance in the space acquisition, planning and construction phases. Testament no doubt, to the amount of technical expertise required for aquaculture farming and the zero margin of error in our government’s pursuit of perfection from planning to execution. We expect the proportion of corporates owning and running aquaculture farms to grow strongly from the current 30% in the years leading up to 2030.

A Glimpse into the Aquaculture’s Future

As an example of things to come, we take a look at the Eco-Ark. “ The Eco-Ark® Abundance (I) is the World’s First Closed-Containment Floating Fish Farm. Aquaculture Centre of Excellence Pte Ltd (ACE) aims to reshape the future of fish farming with eco-friendly, cost-effective and sustainable technology. ACE is the first farm to receive Singapore Food Agency’s permit for an onboard processing unit, reducing food production miles and enables the shortest unbroken cold-chain management for its final products.” ACE produced 20 times more fish than a conventional coastal fish farm – the farm’s higher yield have been attributed to the perks of a closed containment system which protects the fish from weather changes and external environmental threats like plankton boom. The closed containment system has thus enabled greater control over the breeding environment and intensified production density within spatial constraints.

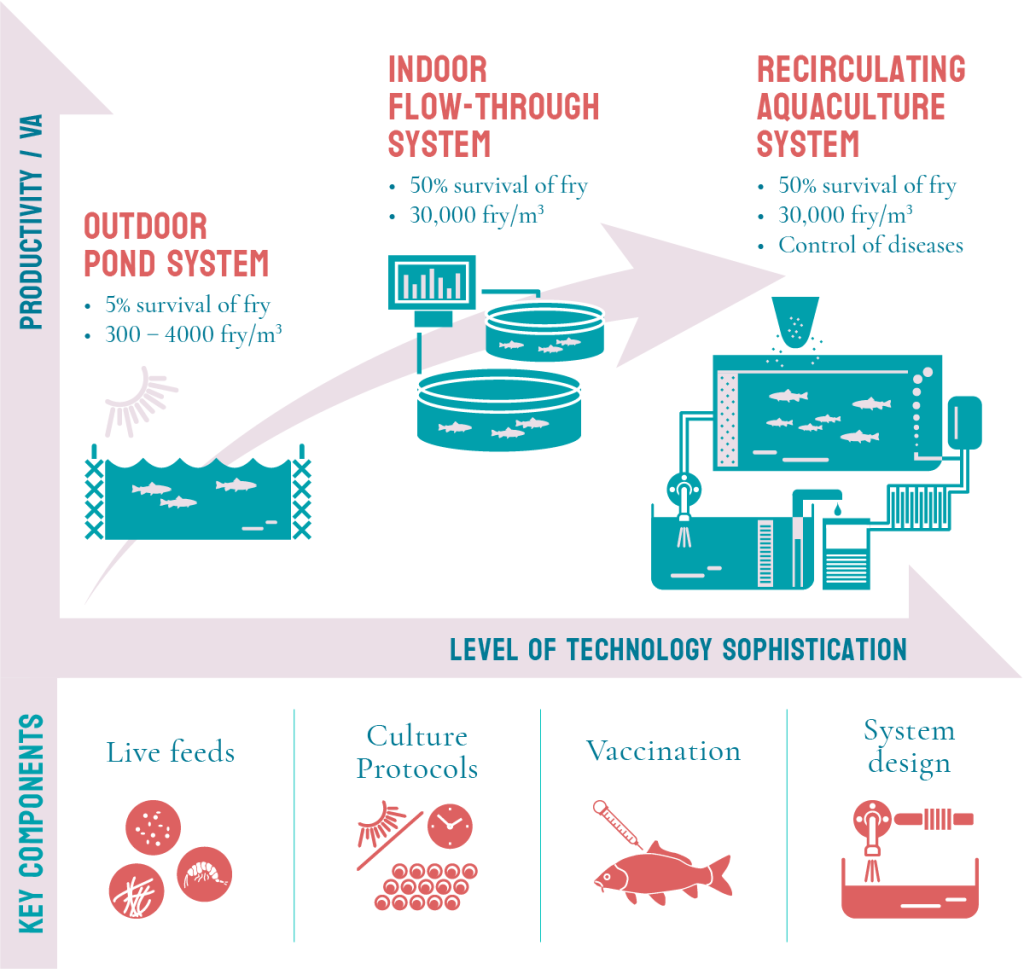

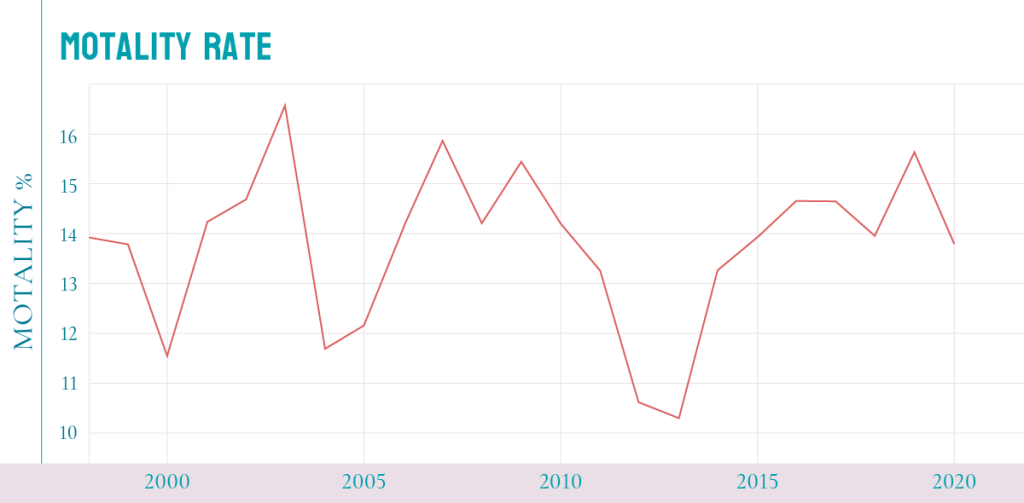

The other often overlooked element in the food supply chain is production wastage. Efforts thus far (possibly futile) have focused on reducing post-production wastage. But the amount of wastage stemming from the pre-production/processing stage is non-trivial. As illustrated above, the fry survival rate of outdoor pond systems is a mere 5%, implying severe wastage arising from a high animal mortality rate. While SFA’s Marine Aquaculture Centre (MAC) has reduced this mortality rate to an impressive 50% by changing the way fish roe is incubated, the average rate remains high, as illustrated in the graph above. Hatchery production has progressed from outdoor pond systems which rely on generous land usage and are at the mercy of weather patterns to a recirculation system which now produces 100 times more fish fry than previously. Also, with healthier fish fries, local farms such as Eco-Ark are able to generate higher yield with lower mortality rates in the grow out phase.

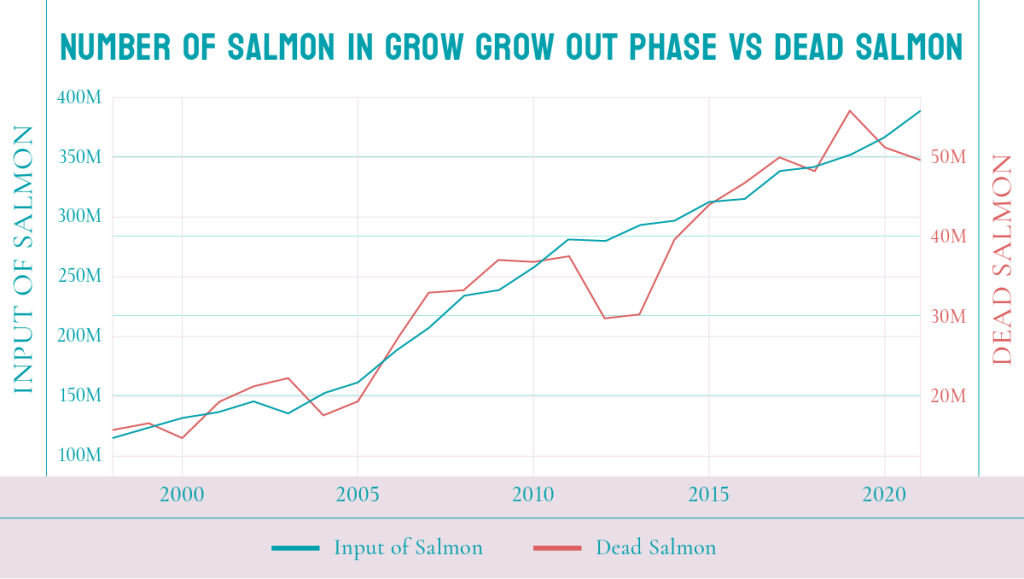

The grow-out phase represents the longest production phase in aquaculture, right up till harvest. Norwegian salmon aquaculture is among the largest export industries in the country and affords ample data to analyse.

The mortality rate is calculated specifically based on dead salmon as a percentage of input of salmon, as illustrated in the graph above. The number of dead salmon is a smaller subset of a category “loss in production of Atlantic Salmon” by the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries. Other loss categories includes farmed fish that has escaped, stolen, been rejected at the slaughter house or counted incorrectly. Dead fish was chosen as a more objective proxy for fish health and welfare.

The mortality rate for Norwegian salmon has hovered around 10% – 17% for the past 2 decades despite technological advances, possibly suggesting improvement to fish health in Norwegian salmon has plateaued.

Moving forward

Inherently, the challenges for aquaculture whether coastal or inland converge on an issue of cost. The operating costs of capturing produce (labour, shipping vessel and fuel, port costs) stacked up against issues of overfishing and dubious labour practices are likely to pale in comparison to land based aquaculture (land cost, water, labour, electricity) or even sea based aquaculture (pollution, overcrowding, disease). The tradeoffs are murky and are far from being fully reflected in just the retail price.

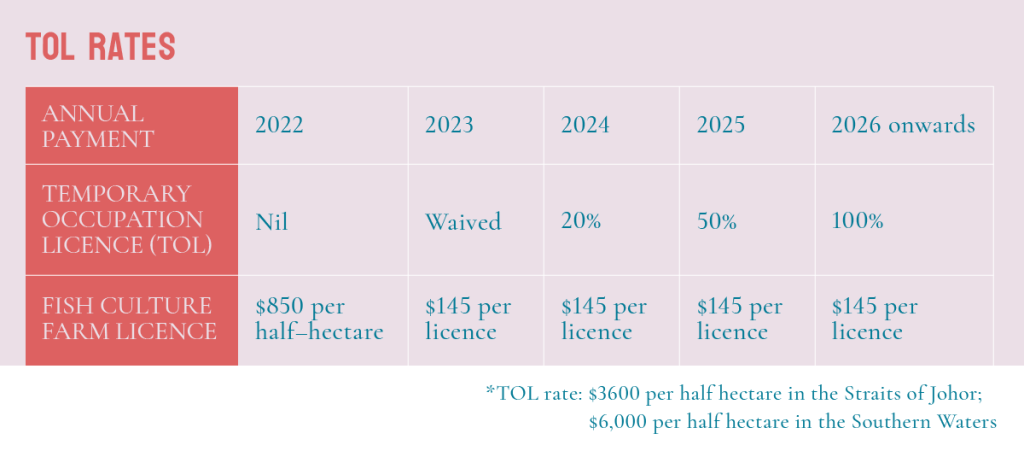

For instance, currently fish farms along the coast of Singapore do not pay for using the sea space, and are subject to a fish culture farm license renewable at $850/ half-hectare annually. While the cost appears low, the establishment has argued that such short (annual) operating leases do not give farmers the confidence to invest in aquaculture technologies with payback periods stretching years out. To incentivise aquaculture farmers, SFA suggested that farmers lock in a longer sea space lease of 20 + 10 years via a Temporary Occupation Licence (”TOL”) at staggered preferential rates as laid out below. The caveat of course, is you have sufficient financial resources to first afford one the “confidence to invest” and navigate the approval process as laid out in SFA’s guide mentioned earlier.

The graph below depicts our local production (data from world bank) and imports of seafood (data from Singstat) over the past decade. The drop in production of around 800 tones (-17%) in 2020 was attributed to “farms adjusting their output due to lower sales during the COVID-19 period.” However, in that same year, imports of seafood increased by 3,000 tones (2%). Ironic. In simpler terms, demand for seafood has not dropped during the pandemic, we have just switched back to imported seafood, hinting of some inelasticity of demand and cost considerations.

To 2030 & beyond

As certain as waves crashing ashore, we expect to see a stronger impetus and trend for corporatising local aquaculture farms given the myriad of regulatory considerations. And of these farms, it’s probable we’d also see a shift towards recirculatory systems based farms – whether land or coastal based. Efforts in the coming years are likely to be devoted towards reducing mortality rates and pre-harvest wastage. If mortality rates in Norwegian salmon are anything to go by, the uplift in production and wastage reduction are likely to come from lowering mortality rates into the teens.

Disclaimer

Please refer to our terms and conditions for the full disclaimer for Stoic Capital Pte Limited (“Stoic Capital”). No part of this article can be reproduced, redistributed, in any form, whether in whole or part for any purpose without the prior consent of Stoic Capital. The views expressed here reflect the personal views of the staff of Stoic Capital. This article is published strictly for general information and consumption only and not to be regarded as research nor does it constitute an offer, an invitation to offer, a solicitation or a recommendation, financial and/or investment advice of any nature whatsoever by Stoic Capital. Whilst Stoic Capital has taken care to ensure that the information contained therein is complete and accurate, this article is provided on an “as is” basis and using Stoic Capital’s own rates, calculations and methodology. No warranty is given and no liability is accepted by Stoic Capital, its directors and officers for any loss arising directly or indirectly as a result of your acting or relying on any information in this update. This publication is not directed to, or intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of or located in any locality, state, country or other jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation.