Singapore Public Housing – Policy Observations

Ken Chan

The Housing & Development Board (HDB) is Singapore’s public housing authority. It is a statutory board under the Ministry of National Development, which underscores the critical role of public housing in nation building. Established in 1960, HDB took over from its predecessor the Singapore Improvement Trust to deal with the housing crisis facing Singapore then.

A HDB flat is a uniquely Singaporean property which is close to every citizen’s heart – a place where 80% of Singapore’s resident population call home. Unknown to many, Singapore description of a “resident population” comprises both Singapore Citizens (SC) AND Singapore Permanent Residents (SPR). With all the noise from the recent spike in property prices in Singapore, we intend to delve deeper to examine some of the pressure points on public housing prices.

With the urgency of the housing crisis of the 1960s behind them, HDB’s role has evolved over the past 6 decades, and so has its policies:

| Year | Restrictions on resale |

|---|---|

| Pre 1971 | Home owners can only sell their flats back to HDB at the original purchase price plus the depreciated cost of improvements. |

| 1971 (Debarment Period) | Owners were able to sell their flats if they have stayed in their flat for 3 years. The Minimum Occupancy Period was pushed to 5 years in 1973 and has remained ever since (excluding PLH). Resale flats were only made available to citizens at this time. Those who sold their flat were debarred from buying another flat for a year. Debarment period was increased to 2.5 years in 1975. |

| 1979 | Debarment abolished. |

| 1989 | Income ceiling for resale flats removed. SPRs allowed to buy resale flats subject to conditions. |

| 1991 | Single citizens above the age of 35 are allowed to purchase resale HDB properties |

| 2013 | Newly-minted SPR have to wait three years before buying a resale public flat |

Singapore’s public housing has evolved over the years, prima facie in step with the changes in our demographics – the proportion of local citizenry has declined over the years as a result of our depressing and continually depressed fertility rate – a phenomenon commonly observed amongst developed countries. The policy decision to expand the scope of eligible purchasers to include SPRs was no doubt a politically charged one, notwithstanding the pressing need for it then to provide stable and affordable housing for local residents. Arguably, the current furore over skyrocketing housing prices public or private alike perhaps has its roots in so many aspects, most possibly the arbitrary divide between local born and bred residents and foreigners/foreign locals however blurred the lines may be. Importantly, it is worth noting that HDB’s original objective and mandate at the beginning of time was as the central point of control for the public housing stock.

What changed?

We argue that the critical change came from the change in HDB’s role as the central arbiter and exchange for public housing post 1971. The shift away from this role with the trend then towards privatisation and a more laissez-faire approach towards public housing changed the landscape drastically.

We believe, it was this key shift in HDB’s role that sowed the seeds for what is now our winter of discontent and the inception of the idea that HDB flats were no longer just used for housing but for investment, retirement and to some extent, speculation. With the entry of market forces came all the attendant ills of speculation and complexities typically associated with private housing. And no financial asset is complete without its own indexation.

Retirement Nest Egg for both State and Individual

Perhaps even more complex, and a tad opaque, is the Singapore government’s land accounting process. Much of the land here belongs to the State and on a freehold basis – freehold insofar as the state continues to exist. HDB as the primary arbiter of public housing, purchases the land from the State on a leasehold basis – most often 99 years (+/- 5 years for construction) and at prevailing market rates as put forth by the Chief Valuer. Simplistically speaking, proceeds received from the land sale by the State are credited directly into Past Reserves to reflect the monetisation of a limited and valuable physical asset. The Reserves are then directed by the Ministry of Finance to the State’s sovereign fund managers to manage as part of its reserve allocation process.

In short, when purchasing a HDB property, one is indirectly and partially contributing to our nation’s reserve building process for posterity. No different for private properties or any other taxpayer but the impact is much more direct. And this process is repeated every 99 years.

In the meantime, HDB then manages the construction process and the subsequent sale of the properties to local residents. The gross sales proceeds (HDB 2020/21: S$4.79bn) have over the years fallen short of gross cost of sales (HDB 2020/21: S$5.45bn) and HDB’s deficit further balloons (HDB 2020/21: S$4.7bn) to provision for temporal or future losses from ongoing construction and other expenses. This deficit is then addressed as part of the overall Government Budget led by the Ministry of Finance as with all other state organs and entities. Notwithstanding the temporal argument of saving for future generations, again this whole process is repeated at the end of the leasehold period – again insofar as the State continues to exist.

The complexity is non-trivial. But as Keynes said, in the long run we’re all dead anyway. HDB’s deficit for the accounting forensically inclined, gives an indication of the quantum of land cost (or sales proceeds on the other side of the coin) involved, but requires quite a bit of reverse engineering based on the the number of units to be constructed and due to be delivered in the future. But we’re obviously not here for that, so let’s take a quick look at some of the data that’s been driving the evolution of public housing.

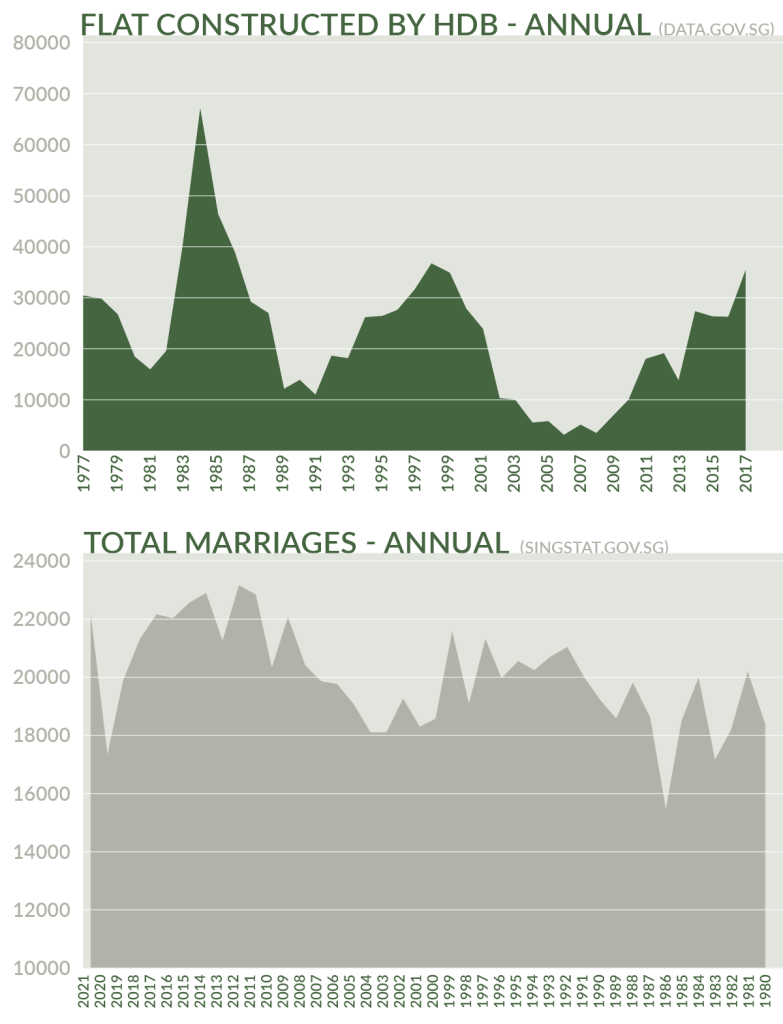

Marriages a proxy for HDB Construction Trends?

While restrictions on HDB flat purchases have loosened over the years, the primary objective remains that of providing housing for families – HDB flats purchasing eligibility is largely restricted to legally married couples or families. There are exceptions made for singles of course, but the primary demand driver for HDB flats remains that of married couples.

The number of marriages has remained fairly stable over the years, with the lows seen in 1986 and 2020 but never declining below the 15,000 mark. It would be difficult to say the same for HDB flat construction, which has fluctuated drastically from the highs of 67,017 in the mid 1980s to the lows of 2,733 during the GFC. Construction has always been a tricky business given the long gestation period – perhaps weddings would be a more stable business to be in.

It’s hard to fathom the inner workings of any public institution, but the data does present a puzzling picture.

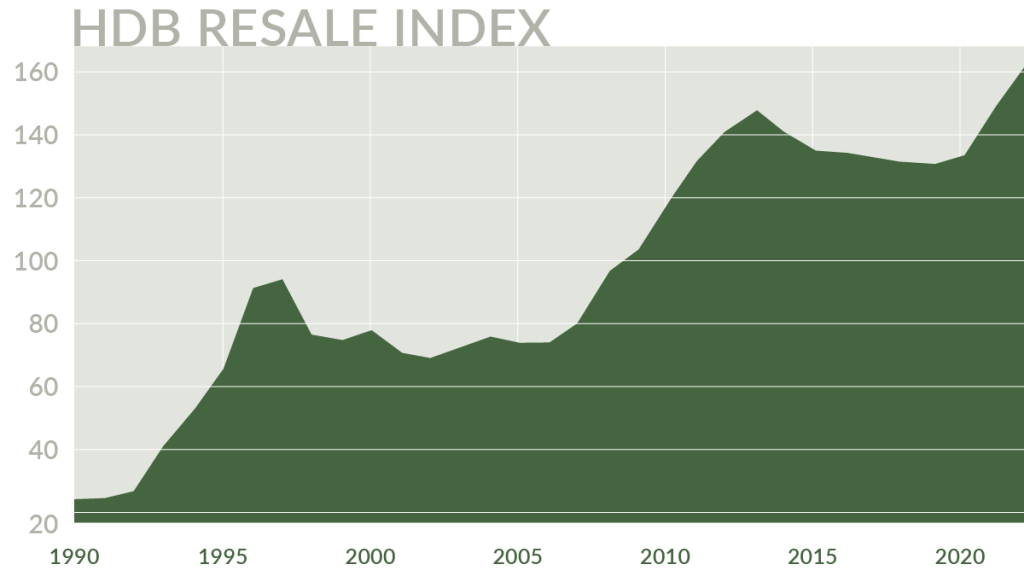

Supply vs Public Price Sentiment

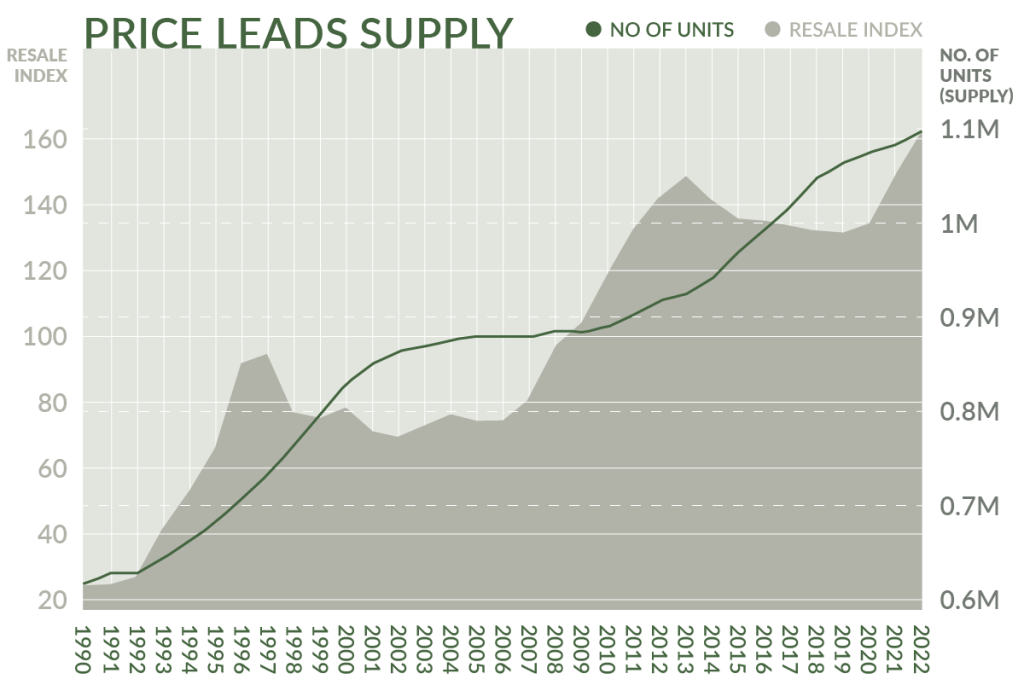

The HDB resale index is calculated with the help of resale transactions across Singapore and represents the evolution of HDB flats in the secondary resale market – a proxy for market forces of supply and demand. Aside from the unmistakable upward trend in prices, there were two peaks – prior to the Asian Financial Crisis and subsequently post GFC. It is here that we see a similar spike in flats constructed by HDB following each of the price peaks. Crudely speaking, one can only speculate that one of the drivers behind flat construction appears to be prices.

Coincidentally, the time lag observed in the spikes in construction and supply of flat units appears to fit in well with the time lag observed in the construction of build-to-order flats of 4-5 years.

Conclusion

Are we too far down the road to change course? HDB’s evolution from a central arbiter and public housing developer to a regulator and spectator of public housing markets has been an uncomfortable one. When the gates were opened to market forces to dictate the pricing of public housing, few expected that supply would also follow suit. The mixed and conflicting objectives of providing affordable housing that can also function as an investment and retirement nest egg have thrown public housing way off its original course. We wait with baited breath for concrete solutions from ongoing parliamentary discussions.

Disclaimer

Please refer to our terms and conditions for the full disclaimer for Stoic Capital Pte Limited (“Stoic Capital”). No part of this article can be reproduced, redistributed, in any form, whether in whole or part for any purpose without the prior consent of Stoic Capital. The views expressed here reflect the personal views of the staff of Stoic Capital. This article is published strictly for general information and consumption only and not to be regarded as research nor does it constitute an offer, an invitation to offer, a solicitation or a recommendation, financial and/or investment advice of any nature whatsoever by Stoic Capital. Whilst Stoic Capital has taken care to ensure that the information contained therein is complete and accurate, this article is provided on an “as is” basis and using Stoic Capital’s own rates, calculations and methodology. No warranty is given and no liability is accepted by Stoic Capital, its directors and officers for any loss arising directly or indirectly as a result of your acting or relying on any information in this update. This publication is not directed to, or intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of or located in any locality, state, country or other jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation.